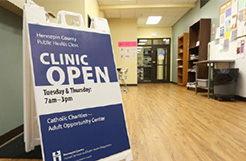

When COVID-19 hit, Hennepin County Health Care for the Homeless (HCH) managers, including Erin Mehta, met to determine how they would respond. HCH operates clinics in nine homeless shelters in Minneapolis. For many people, the program is their only access to health care.

HCH normally functions like an urgent care – people walk-in and ask to be seen. But because COVID-19 is a respiratory illness, managers decided to close the front desk areas and keep the clinic doors shut. Patients had access to a phone at the shelter, and staff put up signage directing people to call to be seen.

In the early stages of COVID-19, if a patient screened positive for respiratory symptoms, HCH would refer them to Hennepin Healthcare. Eventually HCH came up with a system to test for COVID-19 at the clinics. Later, HCH worked with Hennepin County Workplace Safety to re-open HCH as traditional walk-in clinics with resources such as plexiglass dividers, masks, face shields, and full PPE for working with patients with COVID-19 symptoms.

At the same time that HCH was adapting how care at shelter-based clinics was provided, Hennepin County opened two isolation hotels for people who’d tested positive for COVID-19 – one hotel for families (which later became an overflow facility) and one hotel for adults. The hotels served as a buffer for overrun hospitals and helped prevent transmission.

To Erin, the need for isolation space quickly became clear. “People were finding out about the hotels and calling from all over Minnesota, like St. Cloud and Rochester,” she says. HCH staff were tasked with triaging these calls, moving high-risk people to the hotels, and caring for people in their private isolation rooms.

For many people, Health Care for the Homeless is their only access to health care; the program made sure that care continued during the pandemic.

Initially, HCH’s work was focused on helping people who’d tested positive isolate. Isolation involves staying away from other people to avoid spreading COVID-19. Later, HCH’s work expanded to include testing and, in February 2021, they began vaccinating patients and front-line staff.

HCH Program Manager Morgan Smith joined HCH in June 2021 and quickly took on the role of coordinating shelter testing events. The work was dependent on HCH’s partnership with the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH); MDH would let HCH know about an outbreak in a shelter, and Morgan would coordinate a testing event with shelter leadership.

For Morgan, an important aspect of navigating the pandemic was clear and calm communication. Sometimes that meant being transparent and admitting what she didn’t know but would try to find out. “Uncertainty is hard for everyone,” she says. “People want to know what’s going on and what’s coming.”

Morgan and Erin agree that an ongoing challenge was responding to the spikes and troughs of COVID-19 variants. During the Delta variant spike in fall 2021, HCH anticipated maxing out capacity at the isolation hotels. Hennepin County worked closely with Ramsey County to share resources, and at one point discussed merging isolation spaces. Although the merge ultimately did not happen, the counties did partner and mutually refer patients to one another whenever their respective isolation spaces reached capacity.

At the Omicron peak (winter 2021-2022), the isolation hotel and overflow facilities reached capacity. There wasn’t any room at Ramsey facilities either. HCH had to be creative and work with shelters to isolate clients who were testing positive – the solution was to create isolation areas on-site. HCH acted as consultants and helped shelters work through logistics to make sure clients and staff were safe.

In May 2022, Hennepin County closed its adult isolation hotel. Knowing that the resource would no longer be available, HCH staff had tapered off isolation hotel admissions a few weeks before. Closing the hotel was hard for shelters and for HCH staff who’d shouldered responsibility for coordinating isolation. However, at the time of closure, Omicron cases had declined significantly, and nobody required isolation.

Erin stresses that the work was long and difficult. HCH took on responsibilities that were new and constantly evolving. Lots of HCH’s work went unseen by the broader community, but was impactful:

Erin thanks their partners, like Catholic Charities, whose staff were at the isolation hotel overnight, doing room checks and delivering food. HCH also strengthened relationships with hospitals, since the hotel was the only place people experiencing homelessness could isolate.

“I was moved and inspired to see how hard HCH staff worked to get people isolated, tested, and vaccinated,” Morgan says. She remembers a particular day when she shadowed outreach staff at an encampment. She saw nurses bring vaccines in coolers and talk with people about their hesitations. “It was powerful to witness staff building trust with community so that people wanted to get vaccinated,” she says.

Adds Erin, “I learned the power of observing and asking, ‘what is the community saying?’ I’m more cognizant now of who suffers the most during a pandemic and in these types of situations. Listening to community helps us figure out a strategy that aligns and centers their voices.”

Written by: Bo Lopez