Each year, one in five adults experience mental illness. Despite this prevalence, many people are still afraid to talk about mental illness due to shame, misunderstanding, negative attitudes, and fear of discrimination.

Tyrone Patterson, a senior psychiatric social worker with Hennepin County’s COPE and Child Crisis programs, understands the stigma around mental illness too well.

For almost two decades, Patterson has provided clinical care to people with mental illness. During much of that time, he’s also struggled, sometimes silently due to stigma, with his own mental illness.

Today Patterson believes these lived experiences have helped him empathize with people experiencing mental illness. They’ve also made him more committed to breaking the stigma so that people can get the treatment they need.

Read on for Patterson’s story and for a list of local, state, and national mental health resources.

Each year, one in five adults experience mental illness. Despite this prevalence, many people are still afraid to talk about mental illness due to shame, misunderstanding, negative attitudes, and fear of discrimination.

Tyrone Patterson remembers the moment he decided to become a social worker.

It was June 1995, and Patterson, a junior at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, had just returned home from a two-week training in Germany with his Army reserve unit.

When Patterson pulled up in front of St. Coletta of Wisconsin, a home for developmentally disabled adults and children where he’d worked for three years of undergrad, he was swarmed by a crowd of clients.

They were holding balloons, cheering his name, and telling him how much they’d missed him. At that moment, “I realized what an impact I was having on their lives,” Patterson says. “That’s when I declared my major.”

After college, the newly minted social worker held jobs at an alternative high school and at the Bureau of Milwaukee Child Welfare. But then on February 25, 2003, he received a life-changing phone call from the Army reserves: he was being deployed.

Nine days later, Patterson was headed to Fort Carson, Colorado, for additional training, then to Iraq.

In December 2003, 11 months into his deployment, an improvised explosive device (IED) detonated 25 feet from Patterson’s vehicle while he was convoying from Tikrit to Balad. Two months later, in February 2004, a group of soldiers tied Patterson to a pole and taunted him with racial slurs.

These two traumatic incidents took a toll. By the time, Patterson returned home in May 2004, he was experiencing the first symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

One of these symptoms was hypervigilance. Patterson would constantly scan his environment for threats. Unexpected sights, like a deer running across the road, made him especially anxious. “It would take me back to an image of a Humvee windshield trickling with blood after the IED attack,” he says.

Other PTSD symptoms soon manifested. Patterson began having panic attacks while driving his car. And, at night, he’d jolt awake from nightmares, covered in sweat and unable to fall back asleep. He also began withdrawing from family.

Still, he initially resisted help, worried that he’d look weak to Army leadership, wouldn’t get promoted, or would lose his job responsibilities.

Ultimately, though, he summoned the courage to seek help.

In October 2004, Patterson screened positive for PTSD. He began undergoing treatment at the VA, where he received medication and prolonged exposure therapy (PET). At the time, he was working for Dane County Human Services as a child protection social worker.

In June 2008, Patterson accepted a job at the VA Madison Vet Center, providing other veterans with individual and group therapy, marriage and family therapy, bereavement therapy, and sexual assault therapy.

Shortly after accepting the job, Patterson questioned whether he could handle it. “I was hearing similar stories to what I experienced in Iraq,” he explains. “I started having nightmares again.”

To cope, he began taking shots of vodka before bed. “I felt like a hypocrite,” he says. “I had a bottle of vodka under my bed ... And then I’d go to work and tell my clients that it’s not healthy to drink before you go to sleep.”

Still, Patterson continued treatment. One of first homework assignments was to take short drives on the highway. When Patterson started, he could barely drive the length between two highway exits before he would feel a panic attack coming on and have to pull off. But with time, his drives became longer and longer.

It’s now been 15 years since Patterson was diagnosed with PTSD, and like many people, his mental health journey has contained breakthroughs — and setbacks.

One setback occurred in November 2009, after Patterson heard about the mass shooting at Fort Hood, Texas. One of the injured was Dorothy Carskadon, Patterson’s old supervisor at the VA Madison Vet Center. Although she survived, the ordeal set Patterson on an emotional rollercoaster.

Another incident occurred four years ago, when Patterson discovered that one of his clients, a veteran and a sexual assault survivor, had ended his life.

After both incidents, Patterson created a safety plan with his psychiatrist and rallied back. He continues to receive treatment through the VA, including medication management and cognitive processing therapy (CPT).

Today he believes his struggles have made him more empathetic — and more committed to ending mental health stigma.

“I do a lot of presentations about mental illness for the military,” Patterson says, noting that more than 20 veterans end their lives each day. “I share that I take medication. That I don’t think I’m weak … We have to take care of ourselves. I always share the analogy that if you broke your arm you’d go to the doctor, and it should be the same for mental illness.”

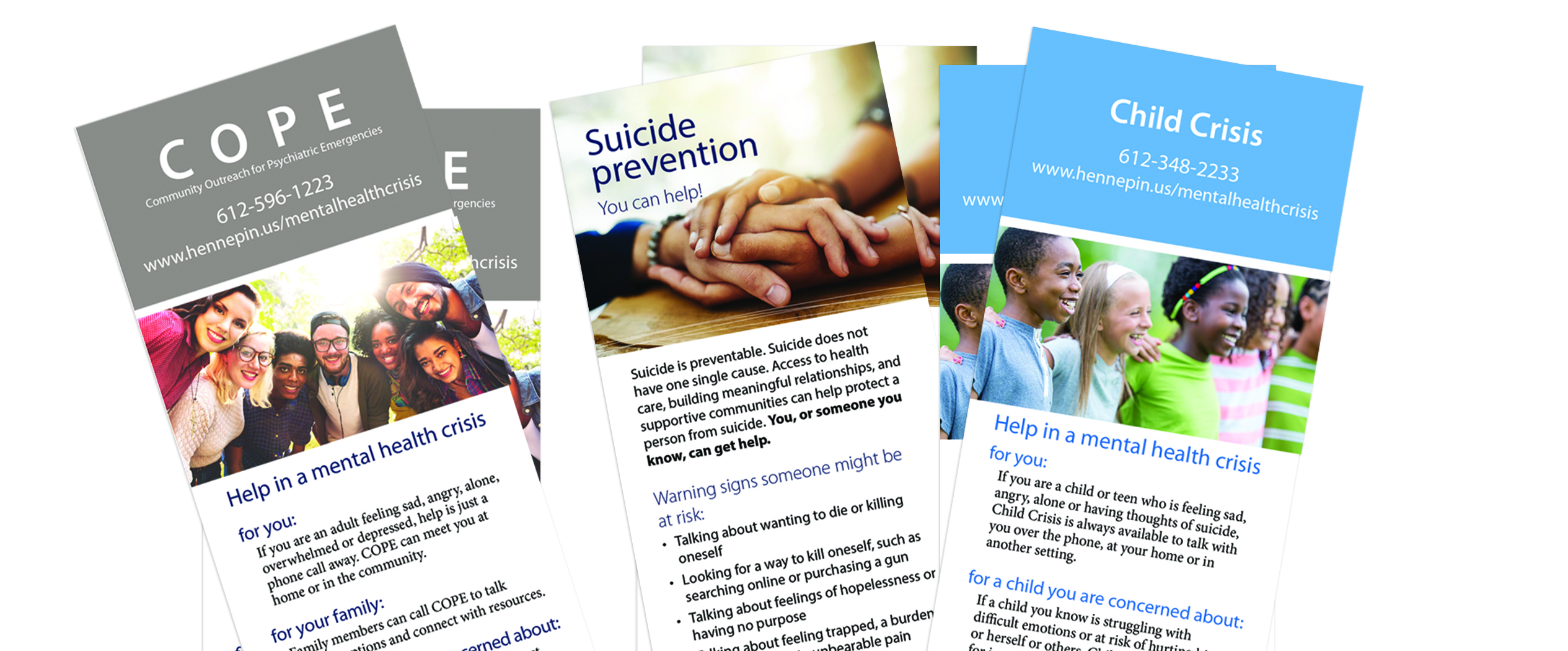

In 2007, Patterson earned his master’s degree in social work from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Since November 2017, he’s been a senior psychiatric social worker for Hennepin County COPE and Child Crisis. The programs provide 24/7 support to people in Hennepin County who are experiencing a mental health crisis. The clinicians in the program, like Patterson, work with clients over the phone and in-person at homes, schools, and in the community.

When appropriate, Patterson shares his personal story with clients. He’s found it normalizes the situation and helps build rapport.

“The biggest hurdle is still the stigma about mental health,” Patterson says. “No matter how hard we try, it’s still like chipping away at a block of ice. But the sooner people get help, the better.”

Read on for a list of local, state, and national mental health resources.

Hennepin County Cope provides mobile, 24/7/365 support for children and adults experiencing a mental health crisis. Add the number to your contact list: 612-596-1223.

The HCMHC is a county-supported facility that serves residents of Hennepin County or people for whom Hennepin County has financial responsibility. As a safety net provider, HCMHC primarily serves people who do not have commercial insurance or who may be uninsured or underinsured. In addition, it welcomes people who may benefit from a flexible service model. It offer scheduled appointments as well as walk-in visits.

Call 612-596-9438 for an appointment or a referral.

Anywhere in Minnesota round-the-clock, seven days a week, people contemplating suicide or experiencing a mental health crisis can text MN to 741741 to connect to a trained counselor.

In the Twin Cities metro area, call **CRISIS (274747) from a cell phone to talk to a team of professionals who can help you.

Outside of the Twin Cities, see the directory for mental health crisis phone numbers in Minnesota by county.

Call or text the National Suicide and Crisis Lifeline for free, confidential support 24 hours a day at 988.

Written by: Lori Imsdahl