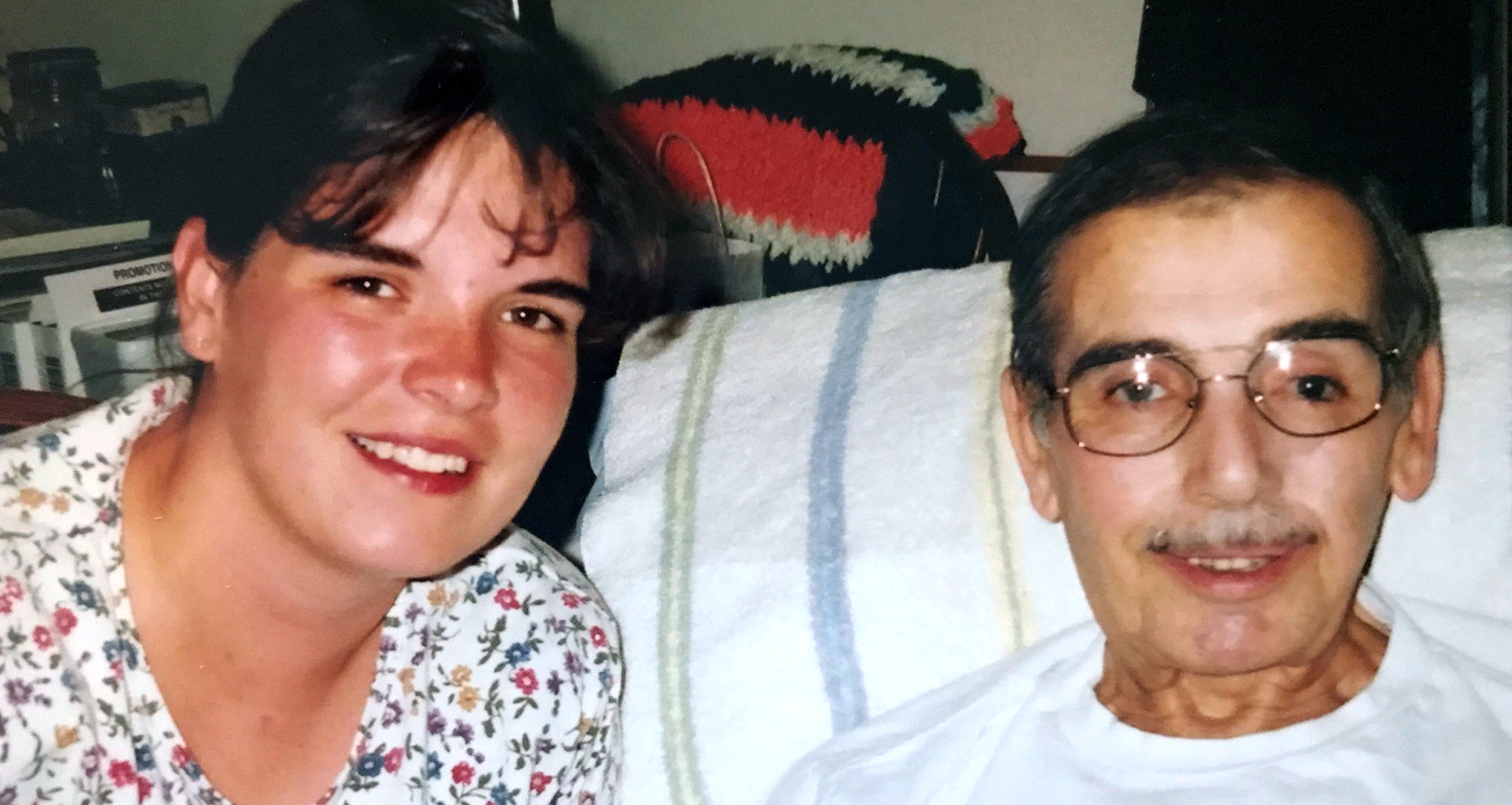

Jeanie’s father, Stan Thompson, was diagnosed with prostate cancer when Jeanie was 17 years old.

A few years before the diagnosis, Stan began having back and pelvic pain – symptoms that are sometimes consistent with advanced staged prostate cancer (early stage prostate cancer usually has no symptoms).

But possibly because of his age – Stan began having these symptoms in his late 40s and the average age of diagnosis is 66 – the doctors didn’t initially screen or test him for the disease.

By the time Stan was diagnosed in 1993, he was 50 years old and his prostate cancer was “distant stage” – a stage IV cancer that has spread to distant lymph nodes, bones, or other organs. The five-year cancer specific survival rate for distant stage prostate cancer is 29 percent.

“My friends were thinking about where to go to college,” Jeanie recalls. But overnight, her thoughts were in an entirely different place.

About one in seven men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer in their lifetime, and one in 39 will die of the disease.

American Cancer SocietyEstimated number

of new prostate

cancer cases

in America

in 2017

Stan Thompson is not an anomaly.

Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer in American men after skin cancer. About one in seven men will be diagnosed with it in their lifetime, and one in 39 will die of the disease.

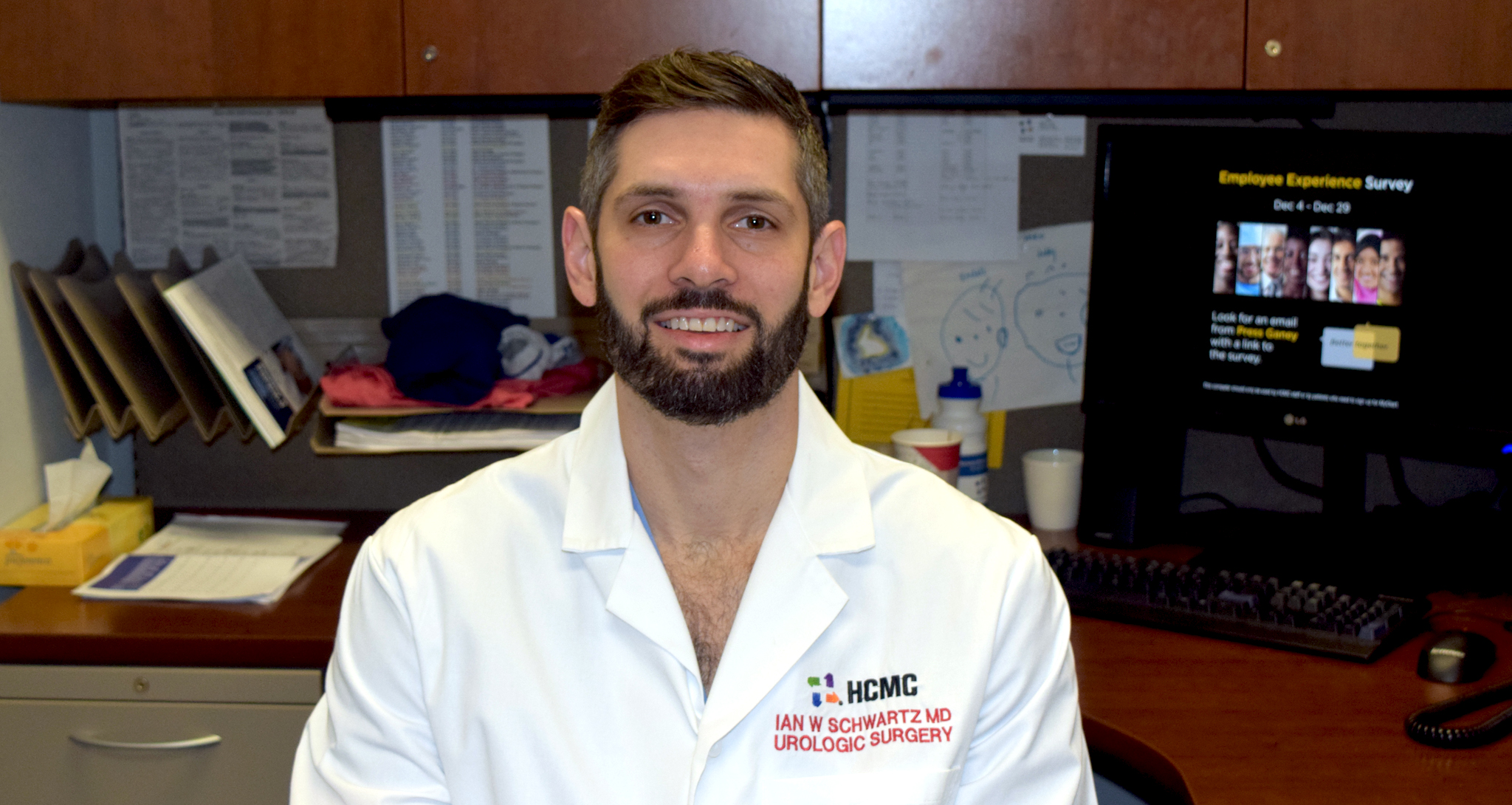

But here’s where it gets tricky: “Prostate cancer, while it’s labeled ‘cancer,’ definitely doesn’t act like most cancers,” says Ian Schwartz, M.D., a urologist at Hennepin County Medical Center. “This is [usually] a survivable cancer.” Indeed, when including all stages of prostate cancer, the five-year cancer specific survival rate is 99 percent.

In most cases the more relevant question, then, is not “How much time do I have to live?” but “How is prostate cancer (or prostate cancer treatment) going to affect my health and day-to-day functioning?” (Potential effects include urinary dysfunction and erectile dysfunction, among others.)

Estimated number

of prostate cancer

deaths in America

in 2017

The U.S. Preventative Task Force gives prostate cancer screening for men age 55 to 69 a C recommendation, meaning that the decision to screen should be an individualized one that takes into account the three main prostate cancer risk factors — age (55+), African American, and family history. That’s because, while screening has the small potential benefit of reducing death from prostate cancer, it also carries some potential harms like overdiagnosis, overtreatment, and treatment-related complications.

At a minimum, Dr. Schwartz says that all men should educate themselves about prostate cancer and have an informed discussion with their doctor after they turn 55 about whether to screen for it.

But if a man has one of the other main risk factors for prostate cancer (African American, family history) he should consider having an informed discussion with his doctor before he turns 55 about getting screened.

“The biggest thing we don’t want to see is the patient who walks into our office with risk factors for prostate cancer who has never had a discussion about getting screened for the disease,” Dr. Schwartz says.

When asked what else men can do to potentially prevent prostate cancer (or prolong its progression), Dr. Schwartz mentions lifestyle.

“To put it in perspective, I say [to patients], ‘Well, what would you do to keep your heart healthy?’” he says. “Because [heart disease] is more likely to kill you than prostate cancer.”

Schwartz mentions reducing red meat intake, eating more fruits and vegetables, and exercise as examples of things that are generally good for the heart — and the prostate.

According to Jeanie, Stan Thompson was “a typical Minnesota man who loved to fish and play hockey.” A Vietnam veteran, he spent 26 years in the U.S. Army before building a successful real estate broker business.

Stan was used to order, appearances, and control, but prostate cancer changed that; eventually, he became too weak to work.

In 1998, when Jeanie was 22, Stan attempted suicide with a firearm. He survived and, with Jeanie’s encouragement, sought care at the Minneapolis VA.

The next few years were “horrible and painful,” Jeanie says. But there was a silver lining; cancer broke down some of her father’s emotional barriers. “He learned to love just to love. He learned to enjoy things just to enjoy things,” she says.

Stan passed away in October 2002, at age 59, nine years after his diagnosis.

Today Jeanie Thompson is executive director of North Star Urology Foundation, a Minnesota nonprofit that provides education and support to people with prostate cancer and other urologic conditions.

“I promised my dad when he was still alive: ‘You made your life count, so I’ll make your death count.’” she says. “If I can save one person, I did my job.”

One way to save lives is to start talking.

“People don’t talk about prostate cancer because [sharing your emotions] feels emasculating,” says Jeanie, who’s observed that it’s often women, not men, who attend prostate cancer events. But not talking about diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, and side effects only compromises disease awareness — and individuals’ mental health.

Speaking of the latter, Jeanie believes her father’s suicide attempt may have been averted if he’d felt more comfortable talking about his experiences or had more people to listen. “[Prostate cancer] is a double stigma,” she explains. “[Men are] not aware of this disease and then, when they are, they’re unaware of who to go to [for support].”

Jeanie’s already talked to her three sons about their grandfather. And, especially because the boys have a family history of the disease, she’s explained to them the importance of talking with their doctors about getting screened for it when they’re older.

“At the end of the day none of this changes unless we talk about it,” she says.

Written by: Lori Imsdahl